The regime executed an estimated 30,000 people. Their ‘trials’ usually lasted minutes

By Shabnam Madadzadeh

September 20, 2017

WSJ – When Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani speaks to the United Nations Wednesday, I will be thinking about the events of 1988, which the regime has tried to erase from history. In school our lessons contained no reference to that summer of blood. But I heard one firsthand story in 2012 from Maryam Akbari Monfared while we were both being held in Tehran’s Evin Prison for our political activities.

“They brought my brother’s belongings—a bag containing his clothes, bloodied and torn from torture,” I recall Ms. Akbari saying. “I will never forget that moment. My parents had gone to visit him, returning instead with his effects. Neither of them could talk. As if they had no words to describe that horrible scene.” By 1988 her brother had been a prisoner for eight years. She said he had been arrested at age 17 for distributing the opposition newspapers of the Mujahedin-e Khalq, or MEK.

The look on Ms. Akbari’s face conveyed the whole scene: the grim mother and father, with no corpse to bury or grave to mourn over. “We will not let this be forgotten,” she whispered.

I am an Iranian political activist. In 2009, as a 21-year-old university student, I was arrested on suspicion of being sympathetic to the opposition. For five years I languished in prison, three months in solitary confinement. Two years after being released in 2014, I was smuggled out of the country by the MEK.

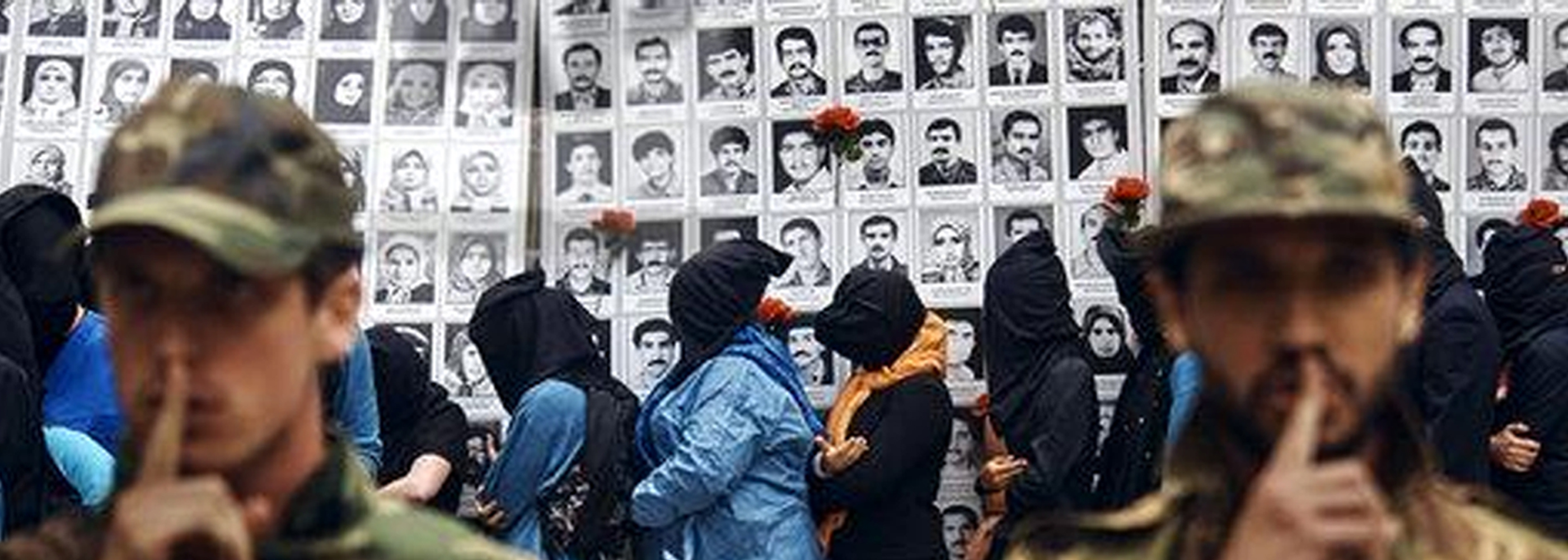

Although the regime has tried to force Iranians to forget 1988, the crimes committed were so vast that this was impossible. An estimated 30,000 people, mainly MEK activists, were executed. Their “trials” usually lasted minutes.

How could their families possibly forget? Before my arrest I met a young woman whose uncle was executed that summer. “To this day,” I remember her telling me, “my entire family stands up in respect whenever his name is mentioned. My uncle was the most human of humans.”

The mass burial sites of 1988 remain largely unknown, and the public is banned from visiting any that have been uncovered, like those in Tehran’s Khavaran area. Nevertheless, mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers have been doing so for the past 29 years.

The massacre exemplified the ruthlessness of Iran’s leaders, many of whom still hold power today. Mostafa Pourmohammadi, justice minister during President Rouhani’s first term, was a member of the 1988 “death commission” in Tehran. The current justice minister, Alireza Avayi, was on the “death commission” in the southwestern province of Khuzestan.

Despite the regime’s efforts, the taboos on discussing the massacre are being weakened, little by little, by young people who had not even been born in 1988. In line with a call by Maryam Rajavi, the leader of the National Council of Resistance of Iran (an MEK-affiliated group), people across the country have been writing, talking and asking questions about the summer of blood. Families who had remained silent for fear of reprisals have begun discussing the victims and revealing the locations of secret graves.

This social movement picked up speed last year when an audio file surfaced of a 1988 meeting between Tehran’s “death commission” and Hossein-Ali Montazeri, who was then the heir-apparent to Iran’s supreme leader. Montazeri decried what he called the regime’s worst crimes, telling the perpetrators that they would go down in history as murderers.

The Iranian people’s demands are simple: Break the silence and stop refusing to admit the mullahs’ atrocities. Talk of a new era in Tehran can be taken seriously only when the ayatollahs are held accountable. The first step is to establish an independent international investigation into the 1988 massacre to bring the perpetrators to justice.

Ms. Madadzadeh is a political activist and former political prisoner in Iran